The Marginal Revolution and a New Theory of Value

TL;DR: We introduce the Englishman William Stanley Jevons, the Austrian Carl Menger, and Leon Walras of France, the three most prominent thought leaders of the “marginal revolution;” a mid-19th century moment in the history of economic thought that introduced subjective “utility” as the theoretical determinant of “value,” and thus price.

A Thought Revolution in the History of Economic Theory

The “marginal revolution” was a pivotal, mid-19th century moment in the history of economic theory. Its most influential insight was that a product or service’s “value,” and therefore price, was not dependent on some large, objective variable that might have gone into its production, such as labor. Instead, value was a completely subjective function of the “utility” that the buyer and seller each assigned to the transaction.

The three economists most closely associated with this breakthrough in economic theory are the Englishman William Stanley Jevons, the Austrian Carl Menger, and Leon Walras of France.

Each of them was a remarkable intellectual. Of their own volition, all three left promising careers in business or government and turned to academia.

Like the true pioneers that they were, they did this at a time when “economics” was not yet the powerhouse social science that it is today.

In a remarkable convergence, at around the same time, they each published in their own country, the pathbreaking texts that helped set the stage for the rise of the neoclassical theoretical orthodoxy that is still taught to students to this day.

The relevant texts were Jevons’ Theory of Political Economy, whose first edition was published in 1871; Menger’s Principles of Economics also published 1871; and Walras’ Elements of Pure Economics, published in 1874.

William Stanley Jevons

William Stanley Jevons life was completely upended in 1848. Born in 1835 into a fairly prosperous Liverpool family, who made their money in the iron ship building trade, Jevons had enjoyed a well-off life prior to that fateful year. In 1848, it came crashing down; the family business fell victim to Britain’s railway speculation crisis of the 1840s, and went bankrupt.

Eventually, this forced a young Jevons, when just 18 years old, to abandon his university studies and migrate to Australia in search of opportunity.

Professionally, he did well there, rising to a lucrative post at the Sidney coin mint. In 1859, however, he quit. He returned to University College in London, where he finished his studies and settled into a life-long career in academia.

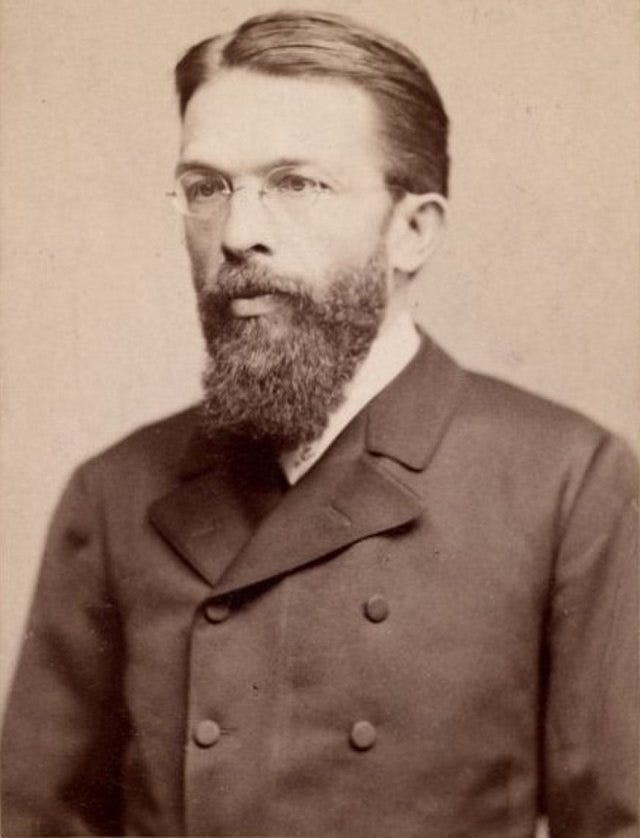

Carl Menger

Carl Menger was born in 1840 in Neu-Sandec, Galicia, territory now part of present-day Poland. He was educated at the Universities of Vienna and Cracow.

Like Herman Heinrich Gossen, he entered the Civil Service, albeit in Austria.

Unlike Gossen, he was quite successful. So much so that when he resigned his post at the Austrian Prime Minister’s office in 1873, the man who had promoted him in government, Prince Auersperg, expressed shock he would want to give it up for academia.

Yet that is exactly what he did. He took up a professorship that year at the University of Vienna. In addition to his advocacy of marginal utility, Carl Menger is today also known as the father of the “Austrian School” of economics, which championed free markets, laissez faire, and individualism, and vigorously resisted socialism.

He is also well known among economic historians for having stood up in his lifetime to hostile opposition to his ideas from the then-prevailing (in German speaking Europe) “German Historical School” which rejected the theoretical approach to economics in favor of historical case studies.

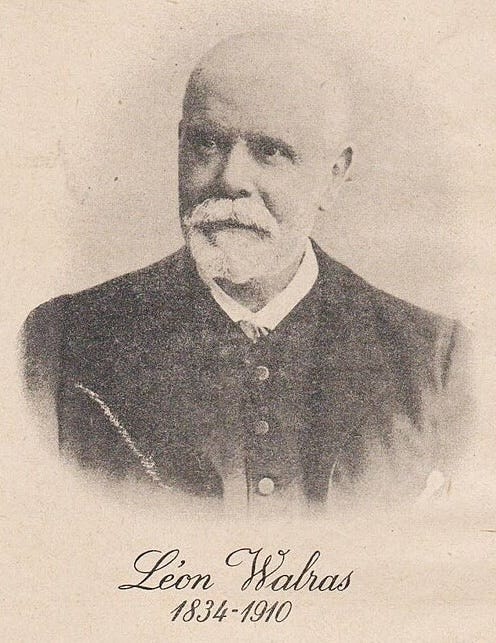

Leon Walras

Léon Walras was born in 1834 in Evreux, France. He was largely self-taught, and never received formal training in economics. Instead, like John Stuart Mill a half-century earlier, it was his father, Antoine-Auguste, who trained him and persuaded him to dedicate his life to turning economics into a science. After a dozen years in what today we would today call “the private sector” (mostly in banking), he finally obtained an academic post in economics in the relative scholastic backwater of Lausanne, Switzerland, albeit in the faculty of law, where he would spend the remainder of professional life.

Utility as the Basis of Value

Again, their contribution was the view that utility, not labor, was the foundation of value.

Jevons in particular could not have been clearer in making this point.

“Repeated reflection and inquiry have led me to the somewhat novel opinion, that value depends entirely upon utility. Prevailing opinions make labour rather than utility the origin of value; and there are even those who distinctly assert that labour is the cause of value. I show, on the contrary, that we have only to trace out carefully the natural laws of the variation of utility ….in order to arrive at a satisfactory theory of exchange.”

William Stanley Jevons, Theory of Political Economy

Similarly, Menger clearly expressed the idea that economic value is a completely subjective measure.

“Value is thus nothing inherent in goods, no property of them, nor an independent thing existing by itself. It is a judgment economizing men make about the importance of the goods at their disposal for the maintenance of their lives and well-being….the value of goods….is entirely subjective in nature.” Carl Menger. Principles of Economics, trans. James Dingwall and Bert F. Hoselitz

Walras and General Market Equilibrium Theory

Leon Walras, too, agreed that utility lie at the core of new theories of value. The scope of his theoretical project, however, did not stop there. His interests extended into the realms of entire markets, and how they might reach equilibrium states.

In particular, he focused on exchange values resulting from free competition, born from the circumstances of laissez-faire, taking the Paris Stock Exchange of his day as his laboratory. Relying heavily on mathematics, he subsequently became the first economist to build models in which individual demand and supply are explicitly aggregated to the level of market supply and demand.

He has been much lauded by subsequent generations of economists for having done so, and economic historians point to Léon Walras as the father of general market equilibrium theory.

Building Blocks for the Neoclassical Ascendancy

The “marginalists’” collective efforts thus gave rise a new theory of value, to replace the now-outdated “labor theory of value” championed by classical economists such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and even Karl Marx.

Their new theories provided the building blocks for the edifice of neoclassical economics. These building blocks included the concept of individual “utility,” a focus on equilibrium states, and the use of mathematics as the primary tool of analysis. That this is the case is well documented by modern historians of economic theory.

Further Erosion of Ethical Thinking

What is less well noted, however, is that concurrent with the development of their new theories, Jevons, Walras, and Menger helped erode even further the relevance of ethical thinking to economics. In turn, they set the stage for their heirs, utilizing the subterfuge of mathematics, to embed the idea of “self-interest” deep into their economic models, where it continues to reside in the 21st century.

We will tell that tale shortly.

What are the Origins of the Idea of “Self-Interest” in Economics?

Before that, however, we’ll take a closer look at the idea of “self-interest,” and how it came to become a linchpin in modern economic theory.

In our next post, we’ll trace its origins back to the European Enlightenment, and explore how it became the philosophical building block of this new approach to economics.

We’ll show that roots of this idea were actually laudable, in the context of the 18th century times in which it came to the fore. Still, our foundational view remains that in the 21st century, “self-interest” is an idea whose “utility” long ago expired as an organizing principal for economic relationships. It needs to be replaced by expansive criteria more appropriate for our modern times.

Further Reading

For those who want to dig deeper, the books and readings that inspired this post are available at The Grove.