Theories of Value

TL;DR: We introduce the “labor theory of value” as a start point for our alternative history on ascendency of neoclassical economics. We note what was sacrificed, in terms of ethical thinking, in the construction of the neoclassical orthodoxy.

An Alternative Take

The events which gave rise to neoclassical economic theory began with a fight over money.

Or rather, with a disagreement over “value.”

From the dawn days of academic economics, the field’s practitioners have felt compelled to develop a “theory of value;” what determines the economic or exchange value of an object, service, or commodity?

And by extension, what determines its price?

The history of “value theory” is extremely relevant to our tale. We shall tell it along two-story lines.

The first story line shall be descriptive; here, we will introduce the mid and late nineteenth century pioneers who laid the foundations of what eventually became neoclassical economics. This is a moment in economic history called “the marginal revolution,” in honor of its most important theoretical advance: marginal utility theory (which we shall explain in our next post).

The second story line shall be revelatory; here, we will provide an alternative take on the history of the marginal revolution as it is most commonly told, which is as a watershed moment in the history of economic theory; one that set the stage for the field to mature into a science in its own right.

The Costs of Constructing an Orthodoxy

While this is most certainly a justifiable interpretation, we shall also shine light on that which was sacrificed, and what fell between the cracks, in the construction of what became a new orthodoxy.

Specifically, what we’ll first see is Benthamite Utilitarianism (already a stripped-down philosophy, relative to its origins in Aristotelian ethics) reduced even further to the economic concept of “utility.”

We’ll further witness a purposeful effort, carried out beneath the banner of “science,” to scrub these new micro-economic theories of any remaining references to ethics and our most treasured spiritual values. In their stead, we’ll see these theorists elevate “utility,” their newly-minted alternative to our moral principles, to the acme of human striving.

We humans, in turn, shall be diminished to one-dimensional consumers scrambling to obtain as much of this new “utility” as we can possibly get our hands on.

This same current of thought will award a quasi-monopoly to mathematics as a way of considering the world around us, even if mathematics is quite often inappropriate as a tool for human understanding; it will then use the tools of mathematics to both embed “self-interest” deep within this new economic theory, and concurrently disguise its presence there.

This new approach will simultaneously strip other modes of inquiry, such as philosophy, psychology and even history, of their expansive upper reaches, and instead permit them to shine just a dim sliver of their explanatory potential into this new microeconomics, and sometimes shut them out all-together.

Spirituality, with its beacons for right living, will not even be allowed a seat at the table

The Labor Theory of Value

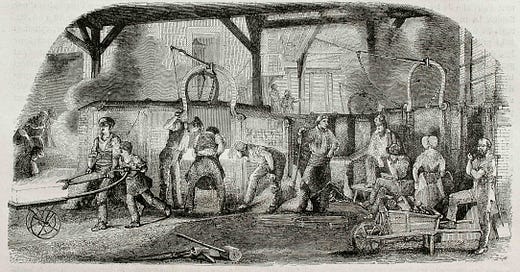

The eighteenth and early nineteenth century classical economists — in particular Adam Smith and David Ricardo — were proponents of a “labor theory of value.”

Economic historians also frequently include Karl Marx among the classical economists, precisely because he too was an advocate of the labor theory of value.

By this they meant that the value of a good, in their theoretical reckoning, was simply a function of the amount of labor it took to produce it:

“The value of any commodity…to use…to exchange… for other commodities is equal to the quantity of labor it enables him [the person who possesses it] to purchase or command. Labor, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of commodities.” Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776

“Labour was the first price, the original purchase money that was paid for all things. It was not by gold or by silver, but by labour, that all the wealth of the world was originally purchased.” Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations, 1776

“Possessing utility, commodities derive their exchangeable value from two sources: from their scarcity, and from the quantity of labour required to obtain them.” David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, 1817

John Stuart Mill advocated a theory of value based on production costs

“As a general rule, then, things tend to exchange for one another at such values as will enable each producer to be repaid the cost of production with the ordinary profit.” John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy, 1885

But because Mill assumed that production costs were almost exactly equivalent to the cost of labor, it is fair to say that he too, was effectively a proponent of a variant of the labor theory of value

“We thus arrive at the conclusion of Ricardo and others, that the rate of profits depends upon …. the cost of labor.” John Stuart Mill, Principles of Political Economy, 1885

Rumbles of Dissent and the Emergence of a Microeconomic View

This view prevailed for a surprisingly long time; almost a century, if we take as its endpoint the marginalist revolution in the 1870s.

Rumbles of dissent, however, had emerged before then.

In the early 19th century, theoreticians began to wonder: what would happen if we put smaller economic units at the center of our theories of value?

What if we shrunk the equation all the way down to a single transaction, between an individual buyer and an individual seller?

In that case, the value of a good or service, rather than being the function of some large, albeit objectively measurable aggregate like labor, instead becomes a function of, well, whatever the buyer and seller decided at the moment.

In other words, it became a completely subjective measure, with price resulting from a personal evaluation of a good’s usefulness and scarcity and thus its worth, or “utility.”

This meant that the focus of economic theorizing, albeit in a spotty, implicit, and uncoordinated way, began to shift away from macroeconomics towards microeconomics; away from grand questions such as the “origins of the wealth of nations” (in Adam Smith’s words) and its distribution among the social classes (landowners, capital and labor, in the conceptualization of David Ricardo), and instead toward the decision-making of individual households, entrepreneurs, and firms, each in turn looking out for its own self-interest within the limits of its capacity to consume or produce.

In slightly more sophisticated language, economists increasingly began to focus on problems of “constrained optimization.”

The Main Characters in the Marginal Revolution

Next week, we shall introduce some the main nineteenth century characters in this “marginal revolution,” as well as their contributions to the emerging science of economics: the Prussian Herman Heinrich Gossen, the Englishman William Stanley Jevons, the Austrian Carl Menger, and the Frenchman Léon Walras.

They set the stage for Alfred Marshall, whom we met briefly in an earlier post: he invented the “market equilibrium” graphs which are a mainstay of a modern economic education, and a workhorse in neoclassical economic theory.

Further Reading:

For those who want to dig deeper, the books and readings that inspired this post are available at The Grove.